Full Interview: The Words Behind Coke Studio

Language is the means through which mystical/poetic messages in our songs have come down to us over generations. When there are errors in this language, then transmission of meaning is impacted. There is a distinct threat that communication of meaning will get stopped. It is important for poetic meanings to continue to be transmitted in our folk and classical heritage.

A conversation between Ahmer Naqvi and Zahra Sabri

Above: Podcast of the conversation – edited by Herald’s Tehmina Qureshi

Naqvi: This is Ahmer Naqvi and I’m sitting here today with Zahra Sabri. We’re going to be having a discussion about several things. Zahra has a long experience working with Coke Studio and specifically working with the translations of the lyrics that were used in the programme over several years. Zahra, to start with, why don’t we talk a little bit about your experience with Coke Studio. How did it start and what exactly were you doing as part of the show?

Sabri: I was doing my Master’s on a Fulbright scholarship at Columbia University in New York in 2010 when someone sent me some videos from Coke Studio. I was intrigued to see that we Pakistanis are doing Persian songs on a non-traditional platform. There was a song by Zeb and Haniya – Bibi Sanam Janam.

I was watching that and found it interesting that the show was also running some translations for that. I felt this was excellent, but noticed that many of these translations were not accurate and did not accord with the poetry of the lyrics. When I returned to Pakistan, having an interest in poetic texts, folk songs and such, I made a point of looking up Arshad Mahmood Sahab. I happened to mention to him that I’ve noticed quite a few errors in the translations that Coke Studio is publishing online and even a few errors in the sung Persian lyrics of songs like Bibi Sanam and Haqq Maujood. I said that it’s absolutely wonderful that Coke Studio is bringing such interesting folk and classical songs to the attention of new audiences, but that if such an important thing was happening, it should happen in a more pristine and immaculate manner. Arshad Mahmood Sahab is a great believer in these things and he agreed with me. He knew Rohail Hyatt and communicated all this to him. Now Rohail Hyatt is himself a perfectionist. He said that he was aware of some of these errors and did want the translations to be done in a more proper manner and that he would welcome being put into touch with a person who had relevant training. So that is how my association with Coke Studio began. It started in Rohail Hyatt’s times and continued till the end of the Strings’ years. I eventually came to translate and retranslate everything that was translated from Season 2 to Season 10. Most of that work has been uploaded as captions on Coke Studio’s YouTube channel, although some of the work from Season 2 and Season 5 still waits upload or replacement on YouTube.

Naqvi: What were you doing your Master’s in? I mean, why were you somebody who could professionally do translations for Coke Studio?

Sabri: I was doing my Master’s in Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies, basically. We took courses in a number of disciplines – Literature, Politics, History. In the process, we had read some classical Persian texts as well. They put a lot of onus on language training in many of these American departments because they wish to foster research at the level of primary texts. So generally, people study some languages alongside whatever discipline they are pursuing. At my department, there was a very famous professor of Urdu – Frances W. Pritchett. She has developed a huge website where she has translated copious amounts of commentaries on Ghalib and Mir’s poetry to help people understand the work of these great poets better. She also knew a number of other people who are the foremost names in Urdu-English translation in South Asia. Hence, through her, I got the opportunity to find out about all this work and learn from it. When I came back to Pakistan, I wished to contribute to this field in some way. At that time, Coke Studio had already become very popular, but it was about to become even more so. It had just started to become very big internationally. There are some niche forums which produce really lovely translations, but these things don’t necessarily reach the general public. It seemed to me that Coke Studio’s songs and translations could have a substantial educational outreach and I felt that if this sort of activity is happening and some resources are being put into educating the general public about the literary treasures of my country, then I should try my best to contribute. And then Coke Studio’s successive producers were also amenable. Rohail and Umber Hyatt, and Faisal Kapadia and Bilal Maqsood all had the desire that a high standard should be aimed for in the transmission of the meaning of these songs. This is why this association proceeded, and lasted as long as it did.

Naqvi: As you say, around the time you came on board, the influence or fame of Coke Studio was starting to grow immensely not just in Pakistan but also at an international level. Hence, in this long association that you had, I would like to know how you perceived your responsibility. As a translator, what did you feel you were trying to achieve, and, secondly, what did you feel the show was trying to achieve?

Sabri: As a translator, I felt I should try to be very, very true to the poetry itself. We were dealing with some huge names in poetry such as Amir Khusrau and Bulleh Shah. These are famous poets and everyone has heard of them. People love to attend qawwalis where Amir Khusrau’s verses are sung, yet most in the audience may only partially comprehend what is being sung. Hence, I sought to translate each and every word as accurately as possible so that people may have a chance to know such beloved poets’ own words more intimately and fully. I felt the translations should be accessible, but not overly casual, and that my words should maintain a poetic feel of sorts, since one didn’t want the translation of words set to music to sound too utilitarian. While mine was not at all a rhymed translation (which usually takes on its own life and departs significantly from the poet’s thoughts in the original poetry), I did try, where possible, to subtly capture the rhythm of the song into the internal rhythm of the translation itself. Of course, I do know that anything I write can never match the power of the original. Translation is the ‘art of failure’, after all, as the American translator John Ciardi has put it. However, the aim was that my translations should be worthy in some humble sense of the original words of these great poets since this is the least we owe to them.

Amir Khusrau’s kalaam

When it came to the folk realm, this seemed to be an opportunity to put to paper many popular songs which may never have appeared in print before. Hence, I requested Rohail Hyatt that we should run these songs not just in standardised Roman script and English translation but also in their original scripts. All the extra effort involved in trying to pin down the exact spellings of Siraiki, Pashto, Brahui or Punjabi words would be worth it because members of the audience who may have heard these languages spoken in their households all their lives but never actually seen those words and sounds represented in written form in their respective scripts would now have the chance to do so. It would thus help to increase literacy in our country’s non-official languages. Rohail Hyatt agreed with this idea, and so we proceeded to do this. Later on, I thought that we should try to provide Urdu translations as well (and not just English translations) for Pashto, Balochi, Sindhi, Persian or difficult Punjabi songs so that our forum can cater to the needs of our wider domestic audiences in addition to those of our international audiences. When Strings became producers, I was able to get their ready agreement for this, and so we began a tradition of translating things into our country’s national language as well as in English.

What was the vision of Coke Studio? I think in some ways it was tied up with the times in which the platform originally developed. They wanted to package Pakistan. Well, not even package… They were, in fact, themselves exploring Pakistan. And through them, the world was exploring Pakistan. The timing of this forum is important. It was not the first time that the folk-pop/rock combination had happened in Pakistan. In the 1990s, there were a number of musical acts such as Junoon who had already taken interest in the traditional poetry and folk music around them. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, with his foray into fusion music, was also very big at that time, and my sense is that pop/rock people such as Rohail Hyatt did used to interact with him socially.

Even earlier, Muhammad Ali Shehki, for example, had appeared in a famous pairing with Allan Faqir to create the hit song Tere Ishq Men Koyi Doob Gaya.

Shehki standing next to Allan Faqir was, we can say, the Meesha Shafi of that time juxtaposed with Arif Lohar.

Even though today the Shehki kind of ‘hip’ might seem much more desi to us, but at that time it may have been the equivalent of Meesha Shafi in some ways. Hence, this kind of collaboration had happened in a dispersed way a number of times before Coke Studio as well, but the point worth thinking about is why our present times became a period when these things came forward on a very big, almost industrial scale.

Naqvi: Yes. This entire process of fusion music you have in Pakistan where, on one hand, you have your pop music which is essentially reacting to global, contemporary forms of music. And on the other hand, you have a thousands-of-years-old tradition of music in folk, classical, etc. And Rohail Hyatt, obviously, has said in many interviews that what lay behind his reasoning in Coke Studio is that he felt he had been playing music here since such a long time but didn’t really know much about the music of his own region. And so, as you put it very rightly, there was a personal exploration of Pakistan.

During all this, of course, there were a lot of different Pakistanis with varying sorts of educational or material privilege who were exploring the history of their own country through this cultural product. You said that you had read some Persian, yet there were a lot of other local languages that were represented in the studio which required that the translation adequately comprehend and reflect the cultural context of the poetry in order to effectively transmit the meaning. On the level of translation, therefore, how much of the process at Coke Studio was an exploration for you and brought new kinds of experiences and realisations?

Sabri: I can hardly describe how rich an educational and artistic experience it was for me, since, over the course of nearly ten seasons, I had the opportunity to work with 13 languages and learn their respective scripts. We worked with Siraiki, Sindhi, Pashto, Punjabi, Brahui, Balochi, Braj Bhasha, Marwari, Bengali, Urdu, Persian, Arabic, and Turkish. Even within some of these languages, there were a variety of living dialects where the language seems to change at every few kos (leagues). Sometimes, the Siraiki that came to us in our songs seemed to lean more towards Punjabi and at other times more towards Sindhi. Sometimes, the dialects of Punjabi also varied. We once worked with a dialect of Pashto from Mardan (in Natasha Khan and Ali Zafar’s Yo Soch) which had features which stood out from the Pashto of Peshawar.

Hence, it was quite interesting to observe all these dialectical and regional variations through the songs that we translated.

The interaction with some of the folk artists themselves was also very rewarding. For example, I discovered Akhtar Chanal Zehri to have an interestingly deeper grasp of Persian grammar than almost any other senior Pakistani artist I dealt with which reveals to us something about places like Quetta and Balochistan vis-à-vis the rest of Pakistan. Artists like Akhtar Chanal Zehri were a mine of information about tribal and nomadic pastoral modes of living which were vital to grasp in order to adequately translate some of the poetic nuances of his songs. His song Nar Bait, whose fast flowing poetry he attributed to the famous Brahui poet Reki, was one of the most challenging and stimulating pieces of poetry I’ve ever had the honour to tackle during all my years at Coke Studio. I took this honour very seriously, and it was one of the reasons which kept me motivated to return to the programme each year despite the sometimes stressful schedule. Because how often is a major Brahui song going to be transmitted to thousands of people across the world and in Pakistan? At the rare moment it does happen, it requires us to try to give it our very best efforts so that people who speak these Pakistani languages may not feel that their songs are not getting the same degree of attention and care as those in more widely-spoken languages such as Punjabi or Urdu.

I had not considered when I came in that I would end up looking at all these languages myself. I had developed a few translations of Persian, Urdu, Braj Bhasha, and very basic Punjabi like Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Rabba Sacchiya in Tina Sani and Arieb Azhar’s Mori Araj Suno, and I offered these to Coke Studio to use for free. But Rohail Hyatt invited me to join the team on a formal basis, be compensated for my efforts and tackle all the songs.

This was quite a challenge for me. A lot of people don’t have the awareness what a major language Punjabi, rather than Pakistan’s national language Urdu, has been for a platform like Coke Studio. There was a time when the majority of songs being released were in Punjabi, which reminds us of what Pakistan is in many ways genuinely about at a more basic level. While Faiz’s Punjabi (which has been accused of being practically Urdu by some of his friends!) was something I felt quite comfortable looking at on my own, it was not so easy for me tackle the Punjabi of other modern and medieval poets with as much confidence. Therefore, Rohail Hyatt put me in touch with the lyricist Asim Raza who has a very rich native knowledge of the language; from there on, a long and active collaboration developed between us, and Asim Raza became my chief go-to person for questions about Punjabi. Punjabi was Coke Studio’s biggest language, but there were also other experts whom I would regularly consult about all our other languages and even about some of the philosophical and religious themes reflected in our Urdu poetry.

Over the years, we built a whole team of such experts and native speakers both inside and outside the academy, and made it a point to credit each and every person who had been kind and generous enough to contribute to our understanding of their languages. We always had to struggle with a very small budget for translation work, so we were only very rarely able to financially compensate people even a little for their valuable help. Mostly we were just getting pro bono help from people, but then university professors seldom demand Rs 3000 or 4000 for these things. They merely say, “We are very happy you came to us. Thank you so much for taking our help! Someone from the entertainment industry actually turned to us for guidance.” Because the resources do exist, you know. Our academic resources may not be as rich as they used to be, but they are still there. We can go and ask more knowledgeable people to guide us to make our work much better. Yet what makes such people so sorry when they watch what is happening in films, television and radio these days is that the new artists don’t even bother approaching them to fill in the gaps in their own knowledge. They just go about doing the mediocre things they do merrily and with impunity.

I would consult all these experts and native speakers (and the artists themselves, of course), but I would always try never to take any piece of information for granted. It was important to try to recheck every single word or spelling myself from some alternate resource and discuss and debate any conflicting information I found with these experts. I ended up building a stockpile of nearly 40 or so dictionaries to consult for all these various languages, because in the end, you see, the responsibility of an error or inconsistency rests with me. The more unfamiliar the language of a song was to me, the more people I would confirm its meaning with in order to triangulate the information. The better the quality of the poetry, the happier I would be to spend more time on it and even to send it to show people with the relevant knowledge based as far apart as Quetta, Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore, Multan, Peshawar, Kabul, Rajasthan, Delhi, Iran, Turkey, New York, Colorado, London and Montreal in the limited amount of time we had available to us for the season.

Naqvi: What you are describing, then, was quite a unique endeavour to rope in these literary/academic types for consultation for a cultural or entertainment product. So, what did you feel was your big takeaway from this entire experience in terms of what you learned about the state of poetry and the arts in Pakistan?

Sabri: I think the state of these things in Pakistan at the moment can to some extent be judged by the fact that a forum like Coke Studio became very big in our times. Our folk and classical literary traditions are very rich and if there had been a platform like this to explore them in the 1990s or 1980s or 1970s, it would always still have held a certain value and cultural importance. But what is it about the times we are living in now that has enabled the unparalleled success of a forum like Coke Studio? The main strength of this forum, besides its technical and aesthetic sophistication, is that they drew on good quality old poetry (kalaam) and its accompanying older compositions to create new songs. This is a point to note – not only has the older kalaam been used, but the same older compositions have mostly also been used, though, of course, creative things have been done with reference to the addition of new kinds of instruments and styles of music. That is the characteristic of most of Coke Studio’s biggest hits. Most new or original songs in Coke Studio have not achieved the popularity of its vintage numbers. If you cut out all the old compositions from Coke Studio, then perhaps a few new (or relatively new) hits remain, but these few hits were by no means enough to make this forum what it did ultimately become internationally. Drawing upon old kalaam and compositions in new and elegant ways and releasing the songs in a very polished, contemporary-looking and social-media savvy way was, I would maintain, a major factor in the forum’s success.

One very good practice which started during the Strings years was to start looking up and crediting all those old composers and lyricists whose work Coke Studio was drawing upon. All the artistic talent and thinking that had been done years ago and which is now reflected in the songs that Coke Studio is showcasing on their forum was thus celebrated. If you read these credits, many of the sources and inspirations that Coke Studio’s songs are honouring become clear to you.

Playlist: Legacy Behind Coke Studio Pakistan (this playlist documents many previous versions of songs and poetry featured in Coke Studio)

The way I see it, one of the chief reasons why a forum like Coke Studio became big during our times rather than any previous period is that today, where we still have some decent musical talent, we are facing a serious crisis of good poetic material for lyrics. The situation we have here in our region cannot be compared to the other places we are deeply familiar with – English-speaking countries like the UK, USA, Canada, and Australia. There, despite the changes in style that occur with each generation, lyric-writing is still strong and original, and new bands and individuals are continuing to come up with work of exceptional quality, expressing with verve and clarity the fresh sentiments of a new generation.

In our region, a generational incapacity among wide swathes of the young population to achieve original and meaningful self-expression in major local languages on this side of the border has (among other financial/political factors) contributed to a weakening of Pakistan’s prominent pop/rock scene. Our national channel PTV, which had provided protection for and promotion of local artists, had lost its erstwhile prestige and influence, and private channels seemed to open the doors to Bollywood to an unprecedented extent by the time Coke Studio emerged on the scene. Meanwhile, a blurring and erasure of language itself on the other side of the border in Bollywood has made lyrics in that industry increasingly formulaic, shallow and meaningless. That is the context in which Coke Studio became so popular on both sides of the border. The forum was delivering songs filled with deep meaning which appealed both to the mind and the soul, and also had a certain restrained and pristine quality visually which left the imagination free to do its own work in painting pictures with words. It was in the midst of a fast dwindling scene for new and fresh music of good quality that a forum like Coke Studio which revived and reinterpreted the old classics became as popular as it did.

Coke Studio has also had a very wide influence. Not only in Pakistan, but also in India. After Coke Studio, we see a greater surge of interest in young urban pop/rock singers in Pakistan to collaborate in one way or another with folk artists. In Bollywood, although technically it is a Hindi-language film industry, the songs have mostly always been in Urdu while languages like Braj Bhasha (what we very vaguely call Poorbi in Pakistan), Marwari, Bhojpuri, and Punjabi occasionally made their way into the films over the years. In the recent couple of decades, however, perhaps due to the rise of bhangra fusion music among the diaspora in the West, Punjabi has interestingly become extremely prominent and mainstream in Bollywood’s music. And after Coke Studio, in addition to the typical kind of Punjabi dance music that we are now used to seeing in Bollywood, there is also much more interest in using Punjabi and Urdu ‘aarifaanah kalaam. People these days like to call this ‘Sufi music’, but I find it impossible to agree with this term. It’s not Sufi music, it’s ‘aarifaanah kalaam.

Naqvi: And what is ‘aarifaanah kalaam?

Sabri: ‘Aarifaanah kalaam means gnostic poetry or mystical wisdom poetry. We can’t say ‘Sufi music’ because music in a culture tends to have the same general characteristics regardless of the kind of song, but the main difference is in the kalaam or poetry itself. Much of our traditional musical tradition is centred on ‘aarifaanah kalaam.

Hence, Bollywood has in recent years, probably under the influence of Coke Studio, started using gnostic or pseudo-gnostic Urdu and Punjabi poetry a lot, and sometimes in very odd contexts, indeed. You probably have an idea of what I’m talking about: films projecting words meant for the Divine – such as “tu mera khuda hai” (You are my God) and “main ne teri ‘ibaadat ki hai” (I have worshipped you) – on to the typical model-type female actors, swaying and sashaying here and there. To the extent that they have – ‘secularised’ this poetry, shall we say? Or perhaps they turned the secular into the sacred, too? I don’t know. (Laughs) It is incomprehensible. It would be difficult to get away with that sort of thing in a more authentic social context, I think.

Naqvi: This point about authenticity leads me back to what you said about trying to maintain as much fidelity to the original as possible in your translation. But how can we objectively know what is or is not an authentic understanding in the context of translation? Even in prose, to translate the basic storyline cannot be said to be the translator’s sole purpose which is also to capture the spirit of what’s been said. Poetry, of course, is that much harder to tackle, since even if you have to explain it to someone in the same language, you lose quite a lot of the effect of the original, and here you’re translating the poetry into another language altogether.

The reason I am especially interested in asking this is that Pakistan is by and large not a monolingual society. Even those of us who are ‘burgers’ are bilingual at the very least and speak some Urdu as well as English. Hence, there are two different worlds that such people are simultaneously inhabiting and the work that you’re doing is obviously creating bridges between these two worlds. As you said, you’re very conscious of the fact that you want to be very true to the texts themselves. But to what extent is that possible? How much is the author as translator present in these interpretations? When you’re making the call of whether a verse is secular/profane or religious, how can you be confident of that decision, especially with regard to the work of authors who have been dead since hundreds of years?

Sabri: That’s a good point. Since I know that my translation is not necessarily going to be published in a book but will run in a very small caption space on Coke Studio’s music videos, I am generally obliged to say the bare minimum about a line of poetry that is being sung. In the early years, I feel, I followed a more restrained and spartan style where my emphasis was mostly on grammatical translation which is accurate communication of meaning at the most basic level. In later years, though, as I developed relatively greater familiarity with the corpus of poetry our lyrics drew on, I felt more and more comfortable with interpreting things a bit more for the audience. Will someone who has no familiarity at all with this culture and its social and spiritual practices understand the verses via the translation as effectively as a person who has much more familiarity? No, definitely not. Given how succinct the translations are, they are more to help people cross linguistic barriers, but cannot always promise to help people cross major cultural barriers with the same efficacy.

You must have some amount of familiarity or at least indirect knowledge of the restrictions of a society with a widespread culture of veiling to fully comprehend the excitement generated for all those smitten by Laila when they glimpse her flashing a glance at them through her veil in Hamayoon Khan’s Laar Sha Pekhaawar Ta.

You have to have some inkling of a literary culture of feigned feminine refusals to amorous advances if you are to adequately understand the reasoning behind the woman’s complaint that Krishna has stolen her bracelet in order to get her attention as we saw happen in Fareed Ayaz and Abu Muhammad’s Kangna. Otherwise, all these poetic references and emotions will seem rather farcical and absurd to you.

Yet, even within our own country, I think different kinds of readers can take away different impressions from a translation I’ve done. I have noticed this at times. For example, perhaps I’ve been reading a lot of Perso-Arabic and Indic poetry and I have a cumulative understanding of the meanings of this kind of literature. I know that what has been literally written is this, but its meaning is usually this. Now take this urban, Anglicised young person who has read very little local literature. He may read my literal translation and take it into another direction completely from what I, as a translator, may have intended, because he is approaching this material in an unimmersed manner. And linguistically, it is indeed possible to do this from the translation that I’ve done. Yet a cumulative understanding of this material has existed since centuries and sometimes five people who are immersed in this literature will all see one and the same thing, and five other people who are not coming to it with this prior immersive exposure to the tradition may not see this thing at all, but five other things which are all different from this as well as from each other! Hence, it depends on your level of immersion. Perhaps even some of the more Anglicised musicians or team members at Coke Studio may be of a similar background to the young person I have described. They may also be seeing or feeling something else at times from what I intended to write. It can be an inevitable result of a different subjectivity and cultural sensibility.

Naqvi: So, is it okay for there to be these two different perspectives on the same thing – shall we say one is correct and the other incorrect?

Sabri: (Pauses) I would say one way of understanding is from within the canon and the other is from outside the canon.

Naqvi: Now you’re being diplomatic, Zahra…

Sabri: (Laughs)

Naqvi: So then, this would be the question – how important is to remain within the canon?

Sabri: Let me answer it this way. I have taught poetry classes formally at universities as well as a series we used to do at T2F called Rekhte Ke Ustaad when its founder Sabeen Mahmud was alive. So, when I’m teaching a class, I would make the argument to the participants that take this one line of poetry – there are ten kinds of literal meaning that can emerge from it and all those would make sense from the perspective of language itself. However, for those who are more immersed in these things, only two or three of these meanings are possible. The rest are just not possible. That is how language works. That is the difference between people who speak languages and those who are learning languages. That’s how a native understanding works, right? So that is what I would say.

Yet it constantly surprises me how many people who love these songs to death continue to read something very different from my translations than what I consciously wrote. But that’s because I have kept it so open in the small space I have in the caption to represent the line’s meaning. And I think, in many ways, Rohail Hyatt had also preferred that the meaning be kept as open as possible. Perhaps that is another reason why Coke Studio also became such a global product. Obviously, in some places (such as in many of Abida Parveen’s songs) it was quite clear that the ‘maula’ being talked about is Hazrat Ali, because Hazrat Ali’s name is explicitly mentioned.

At other times, you have to try to judge whether Hazrat Muhammad is the object of devotion, or is it the murshid, or is it God? ‘Maula’ is an interesting word in the sense that it can literally mean ‘friend’ or ‘slave’ or ‘master/lord’. So, when in contexts where it means ‘lord’, you have to make the call of whether to go for ‘lord’ with a capital ‘L’ or for ‘lord’ in the more general sense with a small ‘l’. Because this is a word we use quite generally, we have to consider many of the religious interpretations, and avoid misinterpretations that can lead us into controversial territory. We have to be careful of all these things while translating.

One thing to note well is that even though the original producer Rohail Hyatt seemed to show a preference for more culturally neutral interpretations and universalist understandings of our poetry, he agreed completely that clear mentions of historical figures like Hazrat Ali should by no means be excised from Coke Studio’s translations. Hence, our effort at translation was very different from, for example, Coleman Barks’ world-famous translations of Maulana Rumi where almost all mention of Rumi’s particularistic religious references to Islam were excised to make his thoughts more relatable for generic Western sensibilities. My translations into English have always been a completely different kettle of fish from that sort of effort at translation.

We have also often dealt with folk legends such as Momal Rano (as in the song by that name by Fakir Juman Shah), Heer Raanjha (as in the song Kheryaan De Naal), Sohni Mahiwaal (as in the song Paar Chanaan De) and Sassi Punnoon (as in the song Ni Oothaan Waale) at Coke Studio.

These legends are common knowledge and those who are deeply immersed in folk music are generally aware of the intricacies of these romances. However, for those members of the audience who may not be familiar with them, I often did wrack my brains over how to make the events being referred to in the song accessible. In later years, especially, as my own style of translation became more fluid and expressive, I tried to communicate as much contextual information in my one-line translation of each verse as possible.

Naqvi: This reminds me of a line within Ni Oothaan Waale where there is a brief reference to the Sohni Mahiwaal legend. The line is ‘raat kabaabaan waali’. So literally, that can be something like ‘The night of the barbecue’. But I remember that in the translation that you guys had put out, there’s an explanation that this actually refers to a specific moment in the story where, I think, a piece of Mahiwaal’s flesh is roasted. Hence, essentially, the context to those lyrics, as you say, is not something people can understand from the literal translation alone.

Sabri: Yes, I remember that. Basically, Mahiwaal was in the habit of bringing Sohni some sort of savoury treat each time he met her. Some accounts say that this was most often fish that he had caught and cooked for her. One night, he wasn’t able to arrange anything of the sort, so he cut a piece of flesh from his own leg to cook for her which she accepted and ate unknowingly. While it sounds like a rather strange occurrence in real life, this act of Mahiwaal’s has been interpreted in literature as one of the great symbols of self-sacrifice and devotion to the beloved. I knew that the word ‘kabaab’, though often used in classical Urdu and Persian in a different sense, is so typical that there was the danger that it might seem almost comic to the uninitiated listener if that line is translated more literally. Hence, I chose to translate it as ‘the night Maahiwal roasted his own flesh for her’.

Here, in this song, some kind of actual notion of kabaab was being talked about in the literal sense of a food item. Classical poetry, however, is full of instances where the word kabaab is used in a much less literal sense. It is very common in Persian to use expressions like ‘dilam kabaab kardi’, meaning ‘You burnt my heart to cinders’. Mir Taqi Mir has famously written in Urdu ‘be-taab ji ko dekha dil ko kabaab dekha; jeete rahe the kyoon ham jo yih ‘azaab dekha’ (I experienced great agitation of mind, I experienced my heart burnt to cinders; how did I even keep on living, having experienced such great torment?). If you have been exposed a little to all this, then you will not instantly associate ‘kabaab’ with an everyday food item, but with a poetic image and your mind will reflect on what it means in that particular context. Hence, rather than seeming comic, the effect on you will be poetic and poignant, as the writer intended.

Naqvi: Where we discuss the uninitiated listener, obviously this entire process of trying to relate to unfamiliar indigenous cultures can be funny as well as enlightening. But when it comes to the musician or artist who is performing these words – what did you feel was the attitude of the musicians and artists towards understanding these sorts of distinctions and understanding the meaning of the poetry being sung generally?

Sabri: Well, overall the education level in our county is very low today, and it has become lower and lower over time. It used to be that even without necessarily going to school in a formal way, people would end up benefiting from a certain sort of training. But now the situation is that our skewed education system is trying to push people to move in the direction of a language like English, which most are unlikely to attain to any very satisfactory degree anyway. You can’t say that too many of our urban types have become great masters and practitioners of the English language. They haven’t. But their understanding of Urdu has become progressively weaker. A lot of young singers who come from small towns or less elite neighbourhoods do have a much stronger grasp of Urdu, especially those of them who also know proper Punjabi.

Some people like to say, “Oh, Urdu is a foreign language for Pakistan, whereas our actual languages are, for example, Punjabi, etc. and if we can’t speak these, then we’ll speak English.” The truth is that if you have good immersion in Urdu, then because Urdu shares both the Persian and Indic canon with other local languages such as Punjabi, it becomes possible for you to have a deeper understanding of these other fine traditions, too. I often think that one of the reasons why Urdu became so popular for a wide swathe of South Asian Muslims (and even for many groups of Sikhs and Hindus for a long period during the colonial and pre-colonial era) was because people saw it is a language which had in some ways quite formally inherited the entire Persian canon. Persian had been removed from its former esteemed position as Mughal India’s official language, but people still felt an affinity and attraction for that old Persian canon. Hence, because of this shared literary canon and vocabulary among Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto etc., if you invest in any one of these languages properly today, then you are leaving the doors of all the other languages open to people as well.

Naqvi: Undoubtedly.

Sabri: But investing in English will not achieve similar results for the simultaneous promotion and protection of knowledge of local languages and traditions, right? Due to this and other reasons, while the Coke Studio tradition has fostered a culture of new artists singing folk material in languages other than those they know or speak (well), making major mistakes in singing these languages has also become a relatively common part of the Coke Studio culture.

Naqvi: When we talk about mistakes, Zahra, are we specifically talking about getting the lyrics wrong?

Sabri: Yes. I’m afraid that many of the artists who have become relatively big names in this past decade have fallen into the recurring habit of getting the basic lyrics wrong. The language most affected is Persian, which is reflective of Pakistan’s growing distance from it and our classical traditions generally. The second most affected language is Punjabi, because artists sometimes just assume that they know it and understand it, but in reality their knowledge is growing increasingly weak. Rarely, we have had serious mistakes in Urdu also.

Due to being involved with the forum for such a long time and due to having a continued sense of loyalty to the forum and to the various teams I have worked with, I don’t think it would be appropriate to publicly go into the full details of what I saw of this tendency behind the scenes. Hence, I will largely reserve my remarks to the tip of the iceberg which is already visible to discerning members of the audience. Suffice it to say that sometimes the mistakes were caught and corrected before the song came out, but there have also been a number of instances where they were not noticed in time and are clearly audible in the songs that have been released for those who are able to notice such things.

Naqvi: What is the nature of these mistakes? I mean to say that one thing is incorrect words and another is incorrect pronunciation. What specifically do these mistakes concern?

Sabri: Oh, I’m not even talking about the pronunciation. Let’s not even go there. In languages like Urdu and Persian, especially, a pronunciation mistake is a very big mistake, if you care about maintaining proper standards. In Pakistan these days, however, so very many old and young people have fallen into the habit of saying ‘Eid Mubaarik’ when the word is clearly ‘Mubaarak’ (with a ‘zabar’ at the end) and not ‘Mubaarik’ (with a ‘zer’ at the end). Hence, we are a fairly problematic country pronunciation-wise, anyway.

What I am more concerned about is major distortion of words and phrases and even the mixing up of lines. A famous she‘r has a particular first misra‘ and a particular second one, for example. But instances have happened where artists have accidentally switched the misra‘ of one she‘r with another in ways that have spoiled and weakened the meaning of the she‘rs. This sort of confusion is such a very basic no-no for a respectable product.

Naqvi: So here, if we talk at a conceptual level – as I see it, Pakistan is a mongrel entity as a nation-state, whereas other nation-states have ethnic homogeneity. I feel that Pakistani pop music emerges from so many of these musicians from upper class families learning music on their own, rather than through any sort of deeply-rooted tradition of Western pop music (unlike what we might, perhaps, find in our Goan community, for example). Our pop musicians are certainly not coming from the tradition of either the classical music of the darbaars or the folk music of the dargaahs. And essentially the interactions they are having with traditional music may have more to do with the oral tradition. For example, if I consider my own relationship with Bulleh Shah, I have mainly encountered him as a lyricist when Junoon recited him, and later when Coke Studio used his words. Hence, it was very late in life that I actually made the effort to encounter Bulleh Shah as a poet on paper.

Sabri: Sure. And the text of Bulleh Shah’s poetry isn’t necessarily fixed either. It’s largely part of a great and extensive oral tradition, and his poetry appeared in the form of published books fairly recently, it seems. As late as the nineteenth century, perhaps.

Naqvi: Exactly. That’s a good point. So, given all these circumstances, if you lifted a misra‘ from here and another from there, and switched them around – to me, that seems a defining quality of the various things that are coming together in Coke Studio. Pop music in Pakistani and maybe even film music in India or Pakistan is something that came together in a rather haphazard manner. And in a lot of ways, when we compare our music in Coke Studio to the way music is made in the rest of the world, we find that in other countries a label makes the music and the corporates give money to put their logo on it. In Pakistan, the corporate is doing the whole thing itself and, as far as my own limited experience is concerned from my observation of the industry generally, the bulk of the money is going towards corporate spending – the billboards, advertising, air space. The money being spent on the actual talent itself is usually quite miniscule. Hence, it is all being done in a very unusual way. The process through which the music is being made is a complete delivery of a corporate advertisement rather than the processes which an actual industry would involve. And the people themselves who are making this music, their idea of identity is something that they are constructing from different sorts of things. Hence, many traditional or established rules understandably become upended in this process. So then, didn’t you sometimes feel that alright, why should we worry so much about what the exact word was that Faiz Ahmed Faiz or Bulleh Shah used? If it’s selling, then it will continue to sell. If it’s a hit, then it’s a hit.

Sabri: Well, I would be sorry if that’s the impression that’s coming across. Maybe, some people might be getting this impression, but I genuinely don’t think our process was as haphazard as that. That is really not how it was.

People use the term ‘hybrid’. Even concerning Urdu, a false theory has been actively popularised that it’s a kind of hybrid language – that it’s a mixture of Persian and other Indic languages. Well, it’s not a mixture. It’s just a regular language, like English. It has a grammar that has grown over a thousand years, and then it has imported higher-order vocabulary from other languages, just as English has done from Latin and French. Hence, Urdu is not really different in any significant linguistic way from Punjabi, English, Persian, French, or Bengali. It’s not a language which randomly developed in some kind of marketplace where Central Asian soldiers were buying things from the local Indian populace. It’s not a lashkari or camp language (as the theory goes) in any meaningful sense. Urdu in its present standardised version has grown through a very natural process from the dialect being spoken around Delhi since hundreds and hundreds of years.

And I would say the same for our pop and film music and even Coke Studio. The process of its development is not really so haphazard. I think the work that the band Junoon has done before Coke Studio (such as Sayyo Ni which became Sayonee in Junoon’s lingo) may have been a bit like that.

Take a little bit from here, a little from there, combine it with a dot of philosophy from a folk source and cast the entire (sometimes crazy) mix all into the mould of some truly wonderful music which catches at your soul. That’s Junoon. That’s not Coke Studio. Coke Studio has mostly been doing already developed songs. We did not develop from scratch most of the songs which became really famous. Full stanzas of older classics were used and maintained in their original form. It was an artistic revisiting and renewal, not an earth-shaking revolution which threw everything helter-skelter.

Hence, things were not necessarily hybrid in the sense that you imply. And as far as concepts of being a mongrel or hybrid culture is concerned, Pakistan is not unique in its ethnic and linguistic diversity. A surprisingly large number of countries are like that. Iran is also very ethnically diverse, with many major languages spoken besides Persian. The same is true for a place like Afghanistan. And India is an example which everyone is well aware of. This sort of diversity doesn’t mean that literary and poetic rules automatically become blurry. In our country, recently what has been happening a little is that when fresh lyrics are being written, some new artists often have difficulty grasping where Punjabi grammar is ending and where Urdu grammar is beginning. Such artists don’t realise that some of what they’ve written is neither Punjabi nor Urdu. That’s the crisis of urban, ‘burger’ Punjabi for you, right?

But in Urdu, the same level of confusion is not seen. If someone blurs Urdu grammar into Punjabi grammar, it would be a deliberate or considered decision rather than an accidental move. Even take the way I am speaking Urdu to you right now. Someone might say that oh, the language has now changed, and people don’t speak the same kind of Urdu anymore. That is not true. Maybe I’m saying one or two things which can be classified as more colloquial than formal, but otherwise there is a great continuity. Always remember, please, that there is a very great continuity.

Hence, the kind of mistakes that I’m talking about are not a result of hybridity of culture. The kind of ‘hybrid’ reflected in the mistakes I’m referring to is not, I would argue, created with the coming together of cultures. Cultures have always been coming together in our region. This is hardly the first time that interaction is taking place and artists are singing in two or three languages. But now what is happening is a lack of knowledge and care. What I refer to as errors are not deliberate artistic/creative decisions. They are simply accidental. Just a mistake. I should give you some examples so you are better able to grasp my meaning.

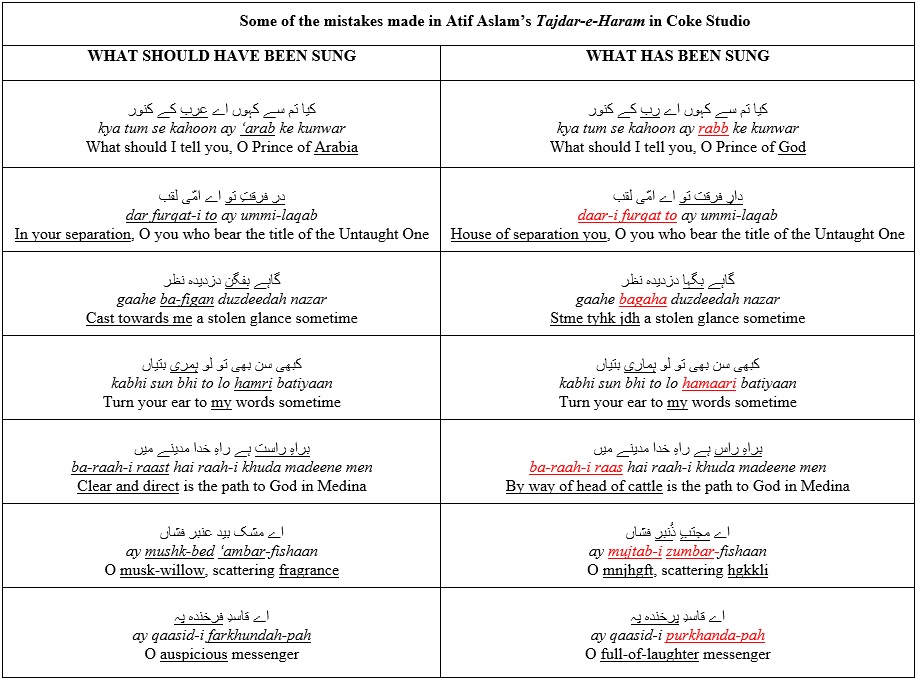

Tajdar-e-Haram is a lengthy song with lots of lines in Urdu, Persian, Braj Bhasha, and Arabic. Atif Aslam has sung most of this very well indeed, in my personal opinion. I know there are some purists who think a qawwaali should just remain a qawwaali, but I think Atif Aslam turned it into a powerful devotional song with a very different flavour, yet still quite stimulating and heartfelt. I also feel that very few people other than him could have sung that song with such expressive emotion. As a friend said, he was not just singing. He was praying. However, very sadly, perhaps because he picked up a rough and faulty Roman copy of the lyrics quite randomly from the Internet rather than taking the trouble to consult some real ustaads, he made an utter muck of quite a few of the Persian lines and even a higher-level Urdu line or two. Utter distortion. Rendering the poetry in those lines meaningless and even comic, if you can find it in your heart to laugh at such an obvious blunder.

Instead of calling the Prophet Muhammad ‘Prince of Arabia’ (‘arab ke kunwar), he mistakenly changed it to ‘Prince of God’ (rabb ke kunwar). While referring to the pain of being apart from the Prophet, instead of singing the correct line ‘dar furqat-i to ay ummi-laqab’ (In your separation, O you who bear the title of the Untaught One), he has sung ‘daar-i furqat to ay ummi-laqab’ (House of separation you, O you who…) which basically results in a rather strange and pointless meaning. Instead of singing ‘gaahe ba-figan duzdeedah nazar’ (Cast towards me a stolen glance sometime), he has mistakenly sung ‘gaahe bagaha duzdeedah nazar’ (Stme tyhk jdh a stolen glance sometime) which really does not mean anything. Further on, he has made even more prominent errors. Instead of singing ‘ay mushk-bed ‘ambar-fishaan (O musk-willow, scattering fragrance), he has ended up singing ‘ay mujtab-i zumbar-fishaan’ (O mnjhgft, scattering hgkkli), and instead of saying ‘ay qaasid-i farkhundah-pah’ (O auspicious messenger), he has erroneously sung ‘ay qaasid-i purkhanda-pah’ which effectively changes ‘auspicious’ to ‘a foot that is full of laughter’.

Then we can take the example of Meesha Shafi. In three of her major Punjabi tracks, she has ended up distorting lines, unfortunately. In Chori Chori in Season 3, for example, she ended up saying something to the effect of ‘Every moment of my beloved, my life’s wir’ (jis da nah ik pal, wir meri jaan da). I was so confused about this when I heard it, because wir is not a recognisable Punjabi word. Now weer is a word – it means ‘brother’. But what on earth is wir? Therefore, I consulted Reshma’s original song, and, sure enough, the implication of the real line is ‘My beloved doesn’t appear before me for a single moment, he doesn’t want me to live’ (disda nah ik pal, wairi meri jaan da). Now this makes proper sense because wairi in Punjabi is indeed a real word! It means ‘enemy’. Hence, the meaning becomes ‘jaan ka dushman’ (mortal enemy), which is an idiomatic Urdu phrase everyone would recognise.

In another song Sun We Balori Akkh Waaliya in Season 7, Meesha Shafi has accidentally turned the word ‘saanhwaan’ (breaths) into ‘raahwaan’ (roads/paths). Madam Noor Jahan’s original line had been ‘saanhwaan wich agg jayi baldi’ which implies ‘The state of my love and passion is so great that it feels as if my very breath is on fire’. But with the change, it means something like ‘The state of my love and passion is so great that it feels as if the roads are burning’. A world of difference. When they heard Meesha Shafi’s version, a friend of mine was wondering why the roads are burning. Was a protest rally taking place in Pakistan where people were setting tires on fire? That’s the effect of a mistake like that on a member of the audience who actually understands the language and poetry of a song, as opposed to others who are just nodding along to the music.

Perhaps the most major mistakes of all, though, are in the even more recent song by Meesha Shafi and Naeem Abbas Rufi in Season 9 – Aaya Laariye Ni Tera Sihriyaan Waala. Now this is a song which is regularly sung in every other household in Pakistan during wedding season. You can’t get more typical and commonplace than this famous and popular song, one could argue. Yet there is a big mistake in the very title line of this song which is repeated throughout. The artists have sung it ‘aaya laariye ni mera sihriyaan waala’ – mera (mine) instead of tera (your). This changes the whole thing and makes it ludicrous. Would a woman refer to her own self as ‘darling bride’ and congratulate herself that her bridegroom has come to wed her. Or would her friends and relatives be calling her this and congratulating her? It’s just… What can you even say about such a basic and fundamental mistake?

Such errors, unfortunately, are seen far too often from our platform. Of course, this is not to say that other artists in other times and on other programmes have never made mistakes. But it is worth thinking about why this tendency is so widespread in Coke Studio, and what is it about these times and this generation of artist that such errors seem to have become almost endemic. What it basically proves is that the artist doesn’t fully understand what he/she is singing. If they did, they wouldn’t make such a mistake. I mean they have a general idea which they speak about in the BTS video, but beyond that, it is sometimes difficult to know for certain how much many of them really understand of the words of their song. If the artist doesn’t completely understand, they can always ask someone who does. But what is worrisome is that many seem to feel that they don’t necessarily need to make that effort.

Think about it – is Tajdar-e-Haram such a difficult and rare kalaam that no one knows what it is about anymore or what the actual words are? Indeed, it is not. Even if you cannot or do not wish to contact the relatives and descendants of Maqbool Ahmed Sabri and Ghulam Fareed Sabri for the lyrics, there must be innumerable qawwaal parties who sing it (and sing it correctly) within the space of a single night within the city of Karachi itself. All it took for me to confirm the real lyrics of the qawwali in blurry places was one brief phone call to Fareed Ayaz and he readily helped me out. It’s about caring enough to get it right. Couldn’t someone from Atif Aslam’s team have made that effort? It is quite a great pity.

Naqvi: So, an artist may have a general sense of what a song is about, but his/her understandings of the specifics and details might be missing. But why is it even important, do you think, for the artist to be faithful to a poet or lyricist’s original words or understand the meaning of each line he/she is singing? I mean, I know we come from a culture where the Qur’an was transmitted orally so fidelity of text and words has been very important to us historically. But for the kind of songs and music we are discussing, why does it matter that with a change of words, some nuances are lost?

Sabri: It matters when you get to the level of singing a totally meaningless line. It’s not just that certain nuances are getting lost in what these artists are singing. They are actually singing some completely meaningless lines. And I wouldn’t say that this care for fidelity to a poet’s original words comes to us only through our culture of preserving the Qur’an through memorisation. Care for words is a pretty universal thing. I don’t think the British or Americans would take too kindly to their own opera singers wrecking the old Italian, German, and Russian classics which they are no doubt frequently called upon to perform in British or American opera houses. If it’s not your language or if you’re unsure of the words, just go and ask someone who does know. Simple! Sometimes, I think that some of our artists probably spend more time thinking about what outlandish costume they would like to wear for their Coke Studio appearance than on how to make sure they have their lyrics right when they turn up to sing on the platform.

You ask why it matters that the words be correct? It matters because communication matters. You understand me because I’m saying words which exist. If I say words which don’t exist at all, how would we communicate, Ahmer?

Coke Studio has promoted a culture where many new singers who would perhaps struggle to earn fame through an original song of their own have found a means to earn fame by re-singing classic material. Through this, at least their voices will gain fame, even if they still continue to struggle to achieve a single original hit outside the Coke Studio platform. Singing things in languages from your soil but which you or your family may not have spoken for at least a generation or two is actually a good thing. At least you’re contributing to popularising these languages among urban audiences, and that is the attractive part of Coke Studio. However, you should be careful to ensure that your efforts are doing more good than harm to all this classical and folk material you’re drawing upon. You should at least take the trouble to understand what you’re singing.

For many of the singers today, however, it doesn’t appear as if they have bothered to understand the songs they are singing – they are simply attracted to the khanak and chhanak (jingle and chime) of the sound of the words without thinking about the fact that these are actual words which communicate meaning to those who speak and understand the language. And this is bringing us to a level which may even prove to be worse than what has happened to Urdu in Bollywood over the past couple of decades.

For the first several decades of India after independence, people who had studied and been trained in Urdu (these were both Muslims and non-Muslims) continued writing lyrics for film songs. Lightweight ghazals continued being written until well into the 1990s. Their lyrics were often quite dignified and meaningful, and some of them even carried some simple philosophical truths about life in a fairly ‘awaami mode. I actually remember picking up a fair bit of my early literary Urdu from these K. L. Saigal type of film songs. (Laughs) Anyway, this work by an earlier generation of Urdu writers helped disguise for a long time what a deep state of decline that Urdu (and, indirectly, spoken Hindi) was sliding into in India. Top actors like Dharmendra and Amitabh Bachchan had such strong Urdu skills that many of us didn’t imagine that such a sharp and sudden decline was around the corner with the generation born a quarter of a century after Partition. But, seemingly all of a sudden, over the past couple of decades, Bollywood started treating Urdu like a stranger it was attracted to, but didn’t really understand. Film songs used Urdu words in ways which made it quite clear that the lyricist did not understand the meaning of the words being used. Urdu had become an exotic artefact. The symbol of a dead civilisation. You used a word because it sounded pretty or grand to you, not because you properly comprehended its meaning. This came as rather a shock to many of us experiencing India only from the outside, who hadn’t seen it coming.

It’s like what attracts kids to glass marbles found lying around in the streets. You pick them up, marvel at their beauty, hold them to the light and liken them to crystal. This is what these Urdu words have become to lyricists, not words but kanche (glass marbles to play with). Alhamdulillaah, maashaallah, subhaanallah, inshaallah, numaaish, farmaaish, aasaaish, aaraaish, khudaai, judaai, zindagi, bandagi, ibaadat, ijaazat, guzaarish –pretty, gleaming little glass marbles to pick up from somewhere, flick around, fit into your verses with more rhyme than reason. Not real words, but pieces of glitter and confetti to scatter all over your lame and meaningless poetry to give it an artificial glitz that your mostly undiscerning audience would not be able to see through. Listening to these songs, it feels like Urdu words are no longer part of a living language, but have become dead artefacts which can no longer speak and defend themselves against misuse.

In Bollywood, it is now very common to hear Urdu words being used in meaningless, ignorant ways, and some of that is now also growing in our culture here at an alarmingly rapid pace. I would even say that, ironically, we may now be going a step further than Bollywood in laxness and ignorance, perhaps because we are trying to be a bit more ambitious than them in our cultural aims without taking care to put in the required effort. Not infrequently now, we are singing words which are essentially non-words. Words which are not just communicating a weak or inaccurate meaning, but which are communicating no meaning at all.

The reason why I ended up noticing these details a bit more than usual was that when I got the unreleased audio of our singers at Coke Studio, sometimes I would have trouble understanding what was being said. It seemed to me that it didn’t make sense. Sometimes the words would be unintelligible to me in a line or two. Hence, I would go back and research all the old versions of a track that I could find to see if it was any clearer. That’s when I would discover that what had been sung by Hamid Ali Bela, Abida Parveen, Ustad Muhammad Jumman, Googoosh, Reshma, Noor Jahan, Tahira Syed, Bilqis Khanam, Begam Akhtar, Mai Bhaagi or Ghulam Fareed Sabri was very different in some places. If there was still time, I would try getting through to the producer(s) – which often became very difficult during production time! – and let them know if a major error was happening. A number of times, we did succeed in alerting the producer(s) in time and were thankfully able to prevent some obvious errors from going through. But at other times, either the song came to me late and I only noticed some of the errors at the last minute when it seemed too late to do anything or alert anyone (such as in Tajdar-e-Haram) or my messages lay around in email inboxes and the producer didn’t get to see them in time. Some serious errors slipped through like this into the final songs released to the public and are now, unfortunately, there for always.

Thus, it was not part of my actual job description to notice and pick out errors in all these Punjabi, Urdu, Marwari, Braj, and Persian songs, but I noticed many of them just coincidentally because I absolutely had to make sense of them in order to translate them properly. Naturally, it was often upsetting for the producer to find out that the artist had made such errors. The songs and lyrics are generally brought to the studio by the artists. Since the studio is handling so very many languages at a time, the producers can only be expected to understand just one or two of them at the general level.

Overall, though, I must credit both Rohail Hyatt and Strings for taking proper notice of these things once they were apprised of it. If possible, they would sometimes try to rerecord the faulty parts, though often it was too late for that. Where errors persisted in the faulty audio, both Rohail Hyatt and Strings agreed that rather than try to cover up the artist’s mistake, the studio should at least acknowledge the fault by keeping the original words in the text of the captions instead of sending out faulty, gibberish text into the cybersphere. Rohail Hyatt would generally advise me to translate what has been sung rather than what should have been sung. But this was within bounds. If what had been sung was not the original but it still made sense, then we would keep that. Otherwise, we would replace it with the original in the text. For example, in Sanam Marvi’s song Sighra Aaween Saanwal Yaar in Season 4, she made one quite serious mistake which members of the audience also noticed. Instead of saying ‘nafi asbaat’ which means ‘negation and affirmation’ (i.e. ‘no god, but God’), she got confused and said ‘nabi asbaat’ (prophet and affirmation) which changes things and spoils the meaning of the stanza quite a lot. However, we kept ‘nafi asbaat’ in the captions because the point is to educate audiences about such an important piece of traditional poetry as ‘alif allaah chambe di booti’ rather than miseducate them. In another place in the same stanza, instead of saying jaan phullaan te aayi (the flowers blossomed), she said something which sounded more like jaan kulaan te aayi (which really doesn’t mean anything relevant). But naturally, we maintained the correct word in the captions.

Hence, both Strings and Rohail Hyatt took these matters seriously. It had become increasingly clear with experience that the old sense of dedication, knowledge, and responsibility was rather on the decline among the newer generation of artists under the age of 40 or 50. In Season 10, therefore, Strings assigned a member of their team to research, listen closely, and bring to their notice during the recording itself if an artist made a single mistake in terms of pronunciation or distortion of a word or line of poetry. Apparently, these were popular practices from the golden days of Radio Pakistan – a poet or knowledgeable person would be hired by the broadcasting company to ensure that the singer makes no mistake of diction.

Naqvi: When we are creating such songs, we are creating meanings at multiple levels. Hence, attention to the method behind it becomes very important, don’t you think?

Sabri: Well, I certainly think that some very basic standards need to be maintained. Some people will say that you know, Zahra, you’re being a purist in your criticism of some aspects of the Coke Studio forum. Purists just don’t like such forums. I find this strange. Who am I to be a purist? What knowledge do I have? I myself was born in the 1980s. I’m hardly some terribly well-trained connoisseur of music, so I couldn’t talk about purism even if I wanted to. No, I’m talking about the minimum acceptable level of responsibility. The words should all be real and express something meaningful.

I’ve spoken already about the most basic level, and will talk a little bit more about this further on. If we go just a little further than this most basic of levels, I would ask this. Can anyone argue with the idea that in order for any musical forum to operate at its fullest potential in these poverty-stricken times, it is absolutely necessary that the persons composing the music or various musical parts of the song should understand the meaning of the words being sung? And that the person singing the words should also understand their meaning well because it will have a definite impact on the emotions with which they will deliver those words? To understand and sing is so very different from singing like a well-behaved parrot. That is the difference between the truly good artists and the mediocre ones. As Fareed Ayaz once said to me, ‘Jis ne dil se naheen gaaya, wuh naakaam ho gaya’ (If you don’t feel the words in your soul, you will fail at singing them well).

It would be good if the whole studio understands the words – the musicians, the producers, the artists, the videographers. But that is clearly not possible with such a huge operation and great multiplicity of languages, and, to be honest, different levels of skill at being able to relate to languages other than your own. It is not essential for everyone to understand the detailed meanings and sentiments behind the lyrics, but at least two people should absolutely understand them in order to do a respectable job – the singer and the composer.

At the non-basic level, thus, what is required is a deep understanding of the meaning of the words being sung. When everyone most directly concerned with the creative and expressive side of the song understands something, they can create something truly beautiful and long-lasting in its fame and impact. If Jaan-e-Bahaaraan was composed by Master Inayat Hussain, it was composed by a person who understood well the basic sentiments of the poet. That’s why he chose that particular composition for it. If Arshad Mahmood had not understood the meaning and message behind Faiz’s Aaj Baazaar Men, he would not have been able to compose that particular music for it which made it a classic. He would have created some more inferior and generic composition for it. Hence, the meanings and moods of all these things need to be kept in mind. Reinterpretations can be great. People make great new versions of old things all the time. But a basic understanding of the meanings is necessary.

Take our recent version of Chha Rahi Kaali Ghata, for example. Hina Nasrullah’s vocals are extremely powerful, yet her expression is so flat. You get very little idea of the meaning of the song from the vocals. The lyrics are filled with an immense amount of pathos and pain. We can even say torment. Begam Akhtar is nearly weeping with pain in her version of the song. Nayyara Noor’s heartfelt version, which has many similar verses, is also sung with the proper feelings that emerge from the poetry. Yet Hina Nasrullah, with her undeniably beautiful vocals, sings it all so calmly, almost as if she is presenting a weather report about cloudy skies and impending rain rather than complaining about how the monsoon season is reminding her of her beloved who is not there to share this all with her. It is clear that the new composer hasn’t understood it either because then he wouldn’t have created such soothing and calm music for this poetry, and added that rather mindboggling new section of poetry to the lyrics. That’s what I’m talking about when I say that when the required understanding is not present, the song mostly falls far short of its potential.

This is the difference between great work, passable work, and pedestrian work. There’s a reason why the Indian producer Muzaffar Ali has been able to achieve what he has with the Raqs-e-Bismal album he did with Abida Parveen. It’s not a fusion album, but it was widely popular. Everything doesn’t have to be fusion to be popular, even today, that’s another thing to remember. It is clear that the producer and composer of the album is actually sitting down and thinking deeply about the meanings behind the poetry. That’s why he is able to bring together Sindh and Lucknow in his collaboration with Abida Parveen in such a beautifully effective way and able to create such new and original classics in culturally impoverished times like these.

This album of Muzaffar Ali’s became immensely popular in Pakistan as well. One song became the soundtrack of a hit Hum TV serial.

And if you go around the boutiques and stores in Karachi, this album is mostly the only other desi thing you will hear playing on the speakers besides Coke Studio. You know that however popular Bollywood seems to have now become among even educated sections of the Pakistani diaspora (who see it as some kind of easily available and ‘fun’ link to the South Asian home culture), it has long been seen as something relatively lightweight and lowbrow in educated circles within Pakistan itself. You watch it every now and then as mindless entertainment, but you don’t make it your religion. Playing Bollywood brings down the tone of high-end stores and restaurants, and customers in Pakistan will often get up and have it turned off. Now Indian classical music and semi-classical music such as the ghazals of Jagjit and Chitra Singh, that’s a totally different matter. There’s a lot of unequivocal admiration in Pakistan for that, of course. Bollywood, however, has generally been looked down upon as largely representing fun and games and not to be considered as serious, respectable art. A similar attitude towards Bollywood exists among a section of India’s own local (not diasporic) population, but the phenomenon somehow seems more widespread in Pakistan.

Naqvi: From this entire discussion of ours, what has come through to me is that language is the means through which these mystical/poetic messages have come down to us over generations. And when there are errors in this language, then transmission of meaning is impacted. There is a distinct threat that that communication of meaning will get stopped. I think that that is what is what your whole point it is – you are arguing not for a purely finicky fidelity to language, but for the importance of poetic meanings to continue to be transmitted.

Sabri: Exactly. That’s it. We cannot emphasise enough the importance of singing things which make – some sense.

Naqvi: Right.

Sabri: The basic level, therefore, is that the artist sings a sentence which actually communicates something. You can’t get more basic than this in your bottom-line requirements of a respectable forum. Singing a word which exists instead of singing a word which doesn’t exist. One might think that this is basic common sense, but you would be surprised to know how often this has not happened in Coke Studio. In Season 8, a band called Seige completely defaced the Marwari classic Khari Neem Ke Neeche. Almost every sentence was distorted in utterly meaningless ways. If you compare the audio to the captions, you will notice significant diversion between the two. Much of the audio is the kind of gibberish that people who speak the language would not be able to make sense of. I have no idea how the singer managed to mess it up so much. He probably picked up the lyrics in Roman script from some totally ignorant fan blog on the Internet and came and sang them in Coke Studio. This is really a very worrying kind of attitude. Clearly, one Marwari word was like any other to this band. Just keep singing ‘hekli’, ‘hekli’ and ‘thaana’ and ‘thaara’, and you have sung a Marwari song. Increase the tempo to some strange and incomprehensible degree, change the mood of that playfully mournful love song to some angst-ridden, race-track number, and voila! You have achieved a ‘fusion’ song. Or so you would like to think. You can’t get more artificial and irresponsible than this.

Alright, Seige is not a particularly famous band and they were never seen in a Coke Studio season again, some may argue. But, unfortunately, our regulars are also known to be careless quite frequently. In Haqq Maujood from Season 3, Sanam Marvi got confused about the components of basic Persian grammar. Instead of saying, “I don’t say ‘I am the Truth’, the Beloved tells me to say it” (man nami-goyam anal-haqq yaar mi-goyad bi-go), she ended up saying something like: “I don’t swyt ‘I am the Truth’, the Beloved swytsmetosyet” (man nami-goyak anal-haqq yaar ni-go yak-bigo). It’s amazing how big artists like Sanam Marvi and Atif Aslam, who can’t even be accused of being super ‘burgers’, think they can just stroll in and just sing whatever sounds vaguely like Persian to them.

If you know even a little Persian, you will hold your head in embarrassment on the artists’ behalf. To come to such a big platform, and not have made sure whether what you are singing is even basically correct. That’s the trouble. Too many artists are just trying to pick up things randomly from audio tapes of older recordings of people like Abida Parveen, instead of trying to get ustaads to write things down for them properly and tell them the proper meaning of things. Sanam Marvi is an amazing talent, a talent which Coke Studio has actually honed and showcased, and her name has now become synonymous with the Coke Studio name, but it is important that the artist try to match the great singers in their understanding of the meanings of songs as well, rather than just their outward style and presentation.

It is not only in the re-singing of older things that we are introducing meaninglessness. Even some of the completely new lyrics can be rather suspect. The worst case I saw was the sub-producer Shuja Haider. In Season 10, he brought before us a stanza of Persian lyrics which he had penned himself. Without knowing any Persian. Imagine that. When I saw that, I was left quite stunned by his audacity. It was complete and utter rubbish. Gibberish of the worst order. I was mystified as to where he might have got it from. Then I learned he himself was the author. This gentleman simply lacked the ability to understand why he shouldn’t write things in a language whose grammar and sentence structure he had no inkling of. He was arguing that the words sounded musical, and it didn’t matter that they made no sense since we were not there to write Mirza Ghalib, after all. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Thankfully, Strings had had the foresight to get this poetry checked shortly before it went into final recording. They politely told Shuja Haider that their platform could not knowingly sanction such artificial and made-up stuff, even if the majority of the audience was unable to distinguish the real thing from the fake in a language they didn’t understand. Thus, they put their foot down and that whole piece got scratched.

Of course, that example is as extreme as you can get. Otherwise, errors in Coke Studio have always been accidental errors caused by carelessness and ignorance rather than a conscious and determined intention to push rubbish onto the audience. Yet what we should also think about is what it is about a forum like Coke Studio that is fostering this culture of frequent errors. I mean, it’s endless. I’ve only given you a small percentage of the examples, believe me. Otherwise, the list is far too long, and anyway the point here is not to compile an exhaustive list of every mistake each and every artist ever made in any song. The point is to shed light on attitudes in the hope that they might change for the better.

When you know what has been going on, it becomes obvious when things look a little shaky. For example, although Ali Zafar is a singer who often seems to understand mood, emotions, and meanings rather better than many singers of his age/background, there is some amount of confusion in his Yaar Daadhi in Season 2. It’s clearly an unfamiliar language for him and you can tell even visually that even he might possibly be wondering whether he has this song exactly right. In the version of this song on his own album, though, a few of these things seem to have been corrected, although the performance still does not reach the basic level it should.

In Season 8, in an absolutely beautiful song called Ajj Din Vehre Vich, Ali Zafar skips a whole word by accident in a very famous she‘r of Ghalib that he recites near the end. Naturally, this affects the meaning for people who are thinking about the meaning. Anyone who knows Ghalib even a little knows this she‘r by heart, but somehow in the rush of rehearsals and recordings at the studio and the environment all this creates, an error like this was made.